Well this is awkward. I set out to research the pervasive activity of ‘doodling’, expecting a plethora of wellbeing benefits in the vein of mindful colouring or mandala drawing. What I found was a swag of web pages extolling the virtues of doodling, but little to no scientific evidence to back up their claims. Of course, this doesn’t mean doodling has no benefits. It just means that science hasn’t quite got round to investigating it yet. Normally I’d avoid writing about an unsupported intervention, but there’s a nifty cognitive bias we humans have called ‘sunk-cost fallacy’ that explains why we have trouble giving up on something we’ve already invested considerable time and effort in. I’ve spent three solid days pouring over journal articles on doodling, so you get to hear what I found.

What is doodling

It’s a trickier definition than you think. A doodle is more than a scribble, but less than a drawing. Doodles are spontaneous, unintentional and unique: produced absently in the moment and never copied from someone else’s work. The lovely thing about doodles is that they’re so flippant and personalised, they’re almost impossible to do badly or well.

Doodles have been found in the margins of medieval manuscripts dating back to the 11th century, and even around the edges of clay tablets inscribed by way-BC Mesopotamian clerks. But while humans have clearly been doodling for centuries, we didn’t have a word for the activity till the 1930s or so. In fact, it wasn’t until the pseudoscience of graphology arose, combined with widespread interest in the Freudian ‘unconscious’, that researchers began looking at doodles as representations of a person’s personality, psychopathology, and unconscious preoccupations.

Left: Delightful doodle of a medieval man getting stabbed in the head with a sword, from a book of treasury receipts c.1290 (The National Archives UK)

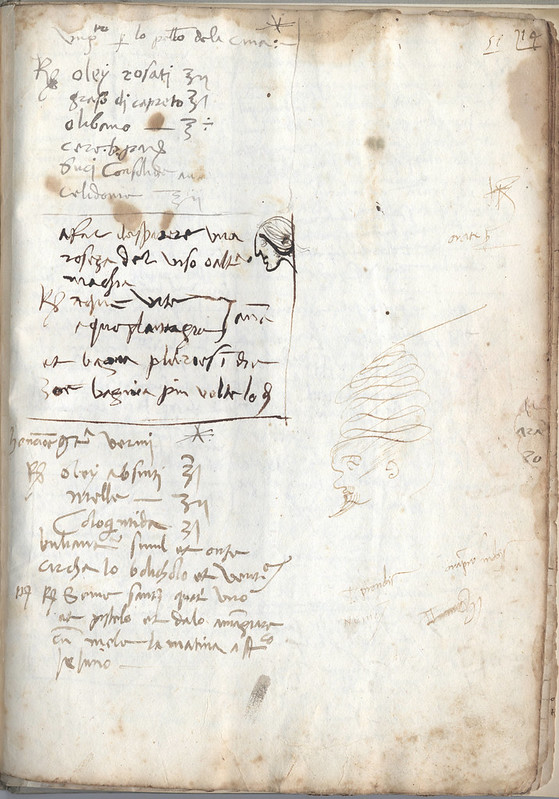

Middle: Doodle from a miscellany of Italian recipes and ephemera c.1614 (University of Victoria Library)

Right: Doodles from a staff member’s page of case notes, Holloway Sanatorium Hospital for the Insane c.1898

In 1938, researchers examined a windfall of 9000 doodles and accompanying letters that had been submitted to a newspaper competition by members of the general public. Analysis of the doodles and letters found that people doodle when they’re feeling boredom, indecision, impatience, or idleness; and that the vast majority of people doodle during a restless or tense state rather then when passive or relaxed. Despite the absolute freedom offered by doodling, most of the 9000 drawings were considered dull, predictable, and could be categorised in one of only a handful of styles and contents. The researchers noted that doodles aren’t limited to images: in fact, underlining, signatures, decorated letters and shading things are all forms of doodling. Most people, however, doodled faces, words or ornamental details; most doodles were small at less than 3.5cm in size; and over half the entries involved writing as well as pictures. Interestingly, this and other studies have found that people tend to have a consistent style and content of doodle. Many entrants reported that they always drew the same thing, or had a limited repertoire of objects or styles that they gravitated towards.

Hypothetically speaking, what might be the benefits of doodling?

Experimental studies into the effects of doodling on wellbeing are almost non-existent, but there are a few floating around that look at other aspects of doodling — plus some researchers and theorists who’ve hypothesised about what the purpose and outcomes of doodling might be.

Doodling and memory recall

Most existing research links doodling to activity in the default network of the brain, and sees doodling as an outcome of a baseline level of cortical activity that kicks in when people are in ‘idle’ mode, and aren’t consciously thinking about anything. It’s the same kind of activity that occurs during daydreaming or mind wandering.

Most web articles claiming the benefits of doodling cite one particular study that found doodling improved memory performance. In the study, people asked to doodle while listening to a telephone call recalled a greater number of memory items than those who didn’t doodle. The suggested explanation was that the doodling task stopped people’s minds from wandering during the very boring task, allowing them to better encode the given information and recall it later. Unfortunately, the task used in the study had participants shade pre-drawn geometric shapes, rather than engage in the type of free-hand doodling that most people do in everyday life. More recent studies, like this one and this one, have confirmed that shading in shapes can indeed help people remember information at about the same rate as writing things down. However, unstructured ‘free doodling’, like most people do in real life, is actually detrimental to memory, and prevents people from remembering information. Interestingly, both these studies found that drawing a picture of the thing you want to remember is far more effective than either doodling or writing the information down.

Doodling to promote symmetry and balance

Alfred Adler, father of humanistic psychology, admitted that he doodled since childhood, and that he always doodled the same thing. He claimed that doodling satisfied the human craving for ‘symmetry’ though a better word might be ‘balance’. Adler thought we seek balance in things like form, shape and number, but also in life, which he said was evidenced through our tendency for antithetical thinking. For example, people seek balance through the creation of oppositional concepts, like man vs woman, heaven vs hell, hot vs cold, above vs below. In reality, these are artificial and largely unrelated constructs, so humans try to understand them by making them relative to one another through a symmetrical opposite. In his book Line Let Loose, David Maclagan says something similar, suggesting that doodling helps us reconcile ‘the dynamic relation between order and disorder, constraint and freedom, public and private’. It might be that doodling when tense, upset, or expectant, then, may help restore feelings of order, balance, and freedom.

Doodling to regain autonomy

Building on Adler’s idea, Guy Manaster suggests doodling helps us find balance in a situation or issue that we cannot otherwise change. We doodle when we are frustrated or ‘stuck’: stuck somewhere we’d rather not be (like a lecture, meeting, phone call, or unwanted encounter), or stuck on a problem we can’t resolve. When we doodle, we go to another place, one of our choosing, and follow our inclinations. In this way, doodling could be seen as providing a sense of autonomy or control over a situation. According to self-determination theory (which underpins much of my own research and work) autonomy is a basic psychological need required by all humans. When we don’t feel in control of our situation we experience unhappiness and reduced wellbeing. But if we can regain a sense of autonomy, like through doodling, it can help us feel better about things. Other researchers have suggested that doodling is a way to speak our mind when a situation doesn’t allow us to express ourselves, or a way to recover a sense of space for ourselves when we’re faced with unwanted external demands.

In this video, artist Shantell Martin explains how her childhood feelings of being an outsider taught her to follow her pen, and eventually doodle her way to increased happiness and a career in the arts.

Doodling and reward pathways in the brain

There’s emerging evidence from neurological studies that both looking at and producing artwork may actually change the architecture of the brain for the better. One exciting pilot study using fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy) found that doodling – along with colouring and drawing – activated reward pathways in the prefrontal cortex, a brain area much studied in relation to addictive behaviours, eating disorders and mood disorders. Both artists and non-artists participated in the study, and all reported feeling increased creativity, enjoyment, relaxation, and problem solving ability following the doodling task. One limitation to the study was that it didn’t include a control task to test the possibility that any old form of ‘doing’ or ‘making’ activity might have had the same result. But it does serve as preliminary support for the idea that brief art-based activities may function as a replacement for some addictive behaviours or mood disorders.

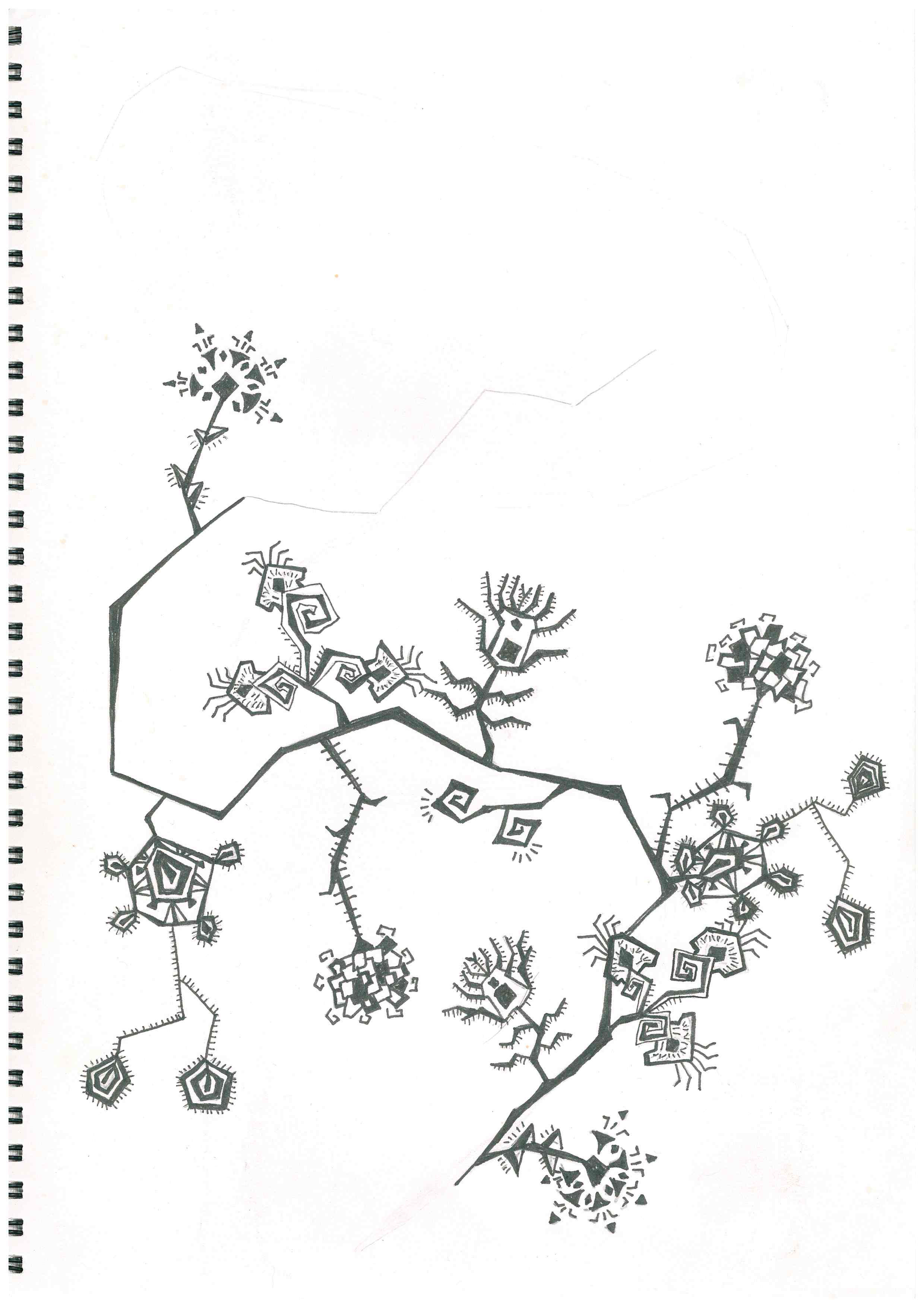

Doodles, meta-doodles and flow

Beyond doodling is a more deliberate and complex activity called ‘meta-doodling’: a kind of doodle on steroids and long-range autopilot. Like your run-of-the-mill doodle, meta doodles are unplanned and improvised, but they’re more prolonged, complex and intensely worked than the average doodle – making them look more planned or professional as a result. They usually occur when a person is unconstrained by time, space, or situation, and many people who create meta-doodles report that they’re undertaken in a trance-like state that’s indicative of flow. Meta doodlers say images emerge unbidden from the paper, and that they just follow the doodle where it leads. Every now and then the doodler may make a conscious intervention, but they soon regain flow and begin re-following the pen. Interestingly, a similar experience is reported by many fiction writers, who claim that their characters exhibit independence and agency. Sometimes these writers say they’re not so much crafting a story as simply following their characters around to report on what they’re doing.

When my kids were young I spent a lot of time waiting around to pick them up after school (I’m talking five kids at three different schools amount of waiting, and one of them was the undefeated Guinness-world-record-holder for extreme dawdling). I kept a notepad in the car and would doodle while waiting. As the pics above show, my own meta-doodles were usually stylised people or words, comprised of repetitive geometric shapes. I didn’t have to think about shapes. Just start with a spot on the page and see where it took me. Mostly I’d doodle in pencil, then trace over it with marker on a different day if I was feeling bored and thoroughly uncreative.

Doodling more effectively

By its very nature doodling is a compulsive and largely unconscious activity. But the key to getting the most out of doodling may be to try and doodle more constructively. So if you’re stuck in a boring meeting or lecture, try doodling representations of what the people around you are talking about. This might help you better remember important information. Alternatively, try to use shading techniques rather than free-hand doodling, as free-hand drawings interfere with memory recall.

While there’s no research into the effects of doodling on stress, anxiety and depression, we can draw on the above ideas (and research from similar activities like colouring or simple drawing) to hypothesise that doodling might be beneficial in reducing some negative mood states. So if you’re feeling stressed or anxious, try putting on a mindfulness meditation or some rhythmic music and doodling repetitive images to regulate your emotions. Fluid, circular doodles may be most useful as these shapes are more calming. At the very least, it’ll give you 20 minutes of quiet time-out all for yourself. 🙂